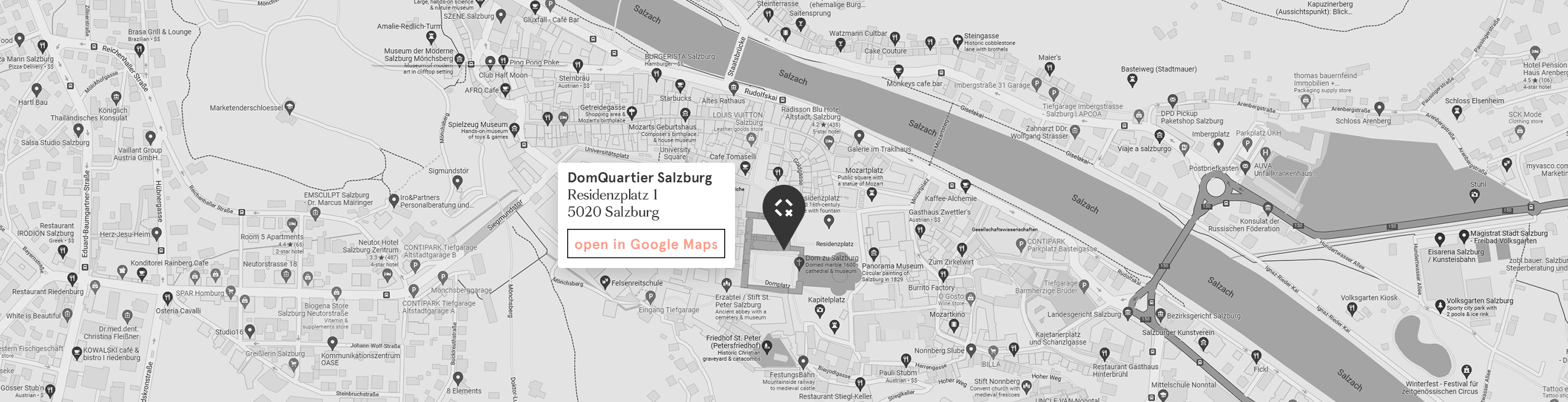

In its 10th anniversary year, the DomQuartier presents in the Residenzgalerie the first guest appearance of the Vienna Kunsthistorisches Museum in Salzburg.

The comprehensive exhibition tells the extraordinary success story of Venetian painting from Renaissance to Rococo. The use of costly pigments, the new loose style of painting and the amazing continuity of typical motifs were essential elements. These qualities are epitomised in the outstanding works of Titian through Tintoretto and Veronese to Canaletto. The works of Titian and his contemporaries have echoed through centuries of European painting and collecting culture. The history of the former imperial collection is the best evidence. Looked at together with individual examples of other art genres, it gives a multi-faceted picture of Venetian art production, possible only in a special exhibition, away from the traditional collection structures of the Kunsthistorisches Museum.

Venetian art from the Renaissance to the rococo, and its special features

The title The Colours of la Serenissima plays on a certain ambiguity, referring on the one hand to the particular use of colour in Venetian painting, and on the other to the actual colours in which the town presents itself to visitors in its mood lighting and the opulence of its luxury items. Portraits of elegant Venetians reflect the self-conception of a successful trading power, evocative landscape painting invites contemplation. New types of religious paintings affect viewers on a highly emotional level.

Success lasting into the 18th century

The success of the Venetian Renaissance was one of the most lasting in European art. A prosperous social class had emerged in the town, keen to show off their wealth and status by means of art-works. With such favourable conditions, “la Serenissima” (as Venice was called) attracted many artists from the region.

The style of Titian and his colleagues soon influenced the conception of Venetian painting well beyond the borders of Venice itself. Right into the 18th century, artists drew inspiration from the colorito alla veneziana, and art collectors strove to acquire 16th-century Venetian paintings in order to be en vogue.

The wealth of Venice and its rise to becoming the commercial hub in the Mediterranean

Until well into the 16th century, Venice was one of the principal trading ports. Palaces and art treasures still testify to the town’s former wealth. Ruled by the Doges, Venice had been expanding into the eastern Mediterranean since the Middle Ages. The harbour saw imports of many luxury goods, including silk, carpets and special pigments, which, along with costly textiles, glass vessels and printed books, were resold in the north. With the expansion of the Ottoman Empire, however, Venice lost more and more Mediterranean territories. The conquest of America by other European powers and the loss of Crete in 1669 diminished the power of the patrician republic. However, Venice managed to defend its territories in the 16th-century wars, and the Venetian patriciate turned its attention more towards the land empire, the terra ferma.

Green Worlds

Ab 1500 führten venezianische Künstler bahnbrechende Neuerungen in der Landschaftsmalerei ein. Ihre Werke suggerieren besondere

Lichtstimmungen, ziehen den Blick der Betrachter:innen in ihren Bann und lassen ihn in die Ferne schweifen. Die Landschaft war dabei nicht bloß Hintergrund, sondern unentbehrlicher Teil der Bilderzählung.

Antike und zeitgenössische Dichter wie Vergil oder Jacopo Sannazaro entwarfen Visionen eines von Hirten bevölkerten Arkadiens, die Künstler in idyllischen Gemälden aufgriffen. In religiösen Werken regten solche Landschaften zur meditativen Kontemplation an und stimmten auf die fromme Andacht ein. Der aus Verona stammende Maler Paolo Veronese malte zwar vor allem Hintergründe mit klassischer Architektur, aber in seinem Spätwerk stellte er eine Wildnis in saftigen Grüntönen dar, in der er die Figuren der unwirtlichen Natur unterordnete. Jacopo Bassano vereinte wiederum mit großem Erfolg religiöse Themen und Szenen mit Bauern vor wiedererkennbaren Berglandschaften des Festlands von Venedig.

Sensual pleasures of the gods

Thanks to prominent publishers such as Aldus Manutius, 16th-century Venice developed into a centre of book printing. Ancient texts spread rapidly, and collectors educated in the humanities increasingly commissioned works with mythological themes, which they admired for the sensuous quality of their accounts of amours amongst the gods and goddesses. Scholars and artists would often conduct cultivated conversations in luxurious rooms, surrounded by small bronzes of ancient figures.

It was against this background that Titian, demonstrating his inventiveness, painted sensational pictures based on Ovid’s Metamorphoses. Their immediate success was reflected in numerous variations, which he carried out in collaboration with his workshop. Andrea Schiavone’s painting Diana and Actaeon, too, follows Titian’s work in both subject and style, and a century later, Giulio Carpioni made reference to an important early work by the master.

Flawlessness in female portraiture

Female portraits by Venetian painters generally showed women of supreme beauty. The ideal beauty of the Italian Renaissance was seen as having blond hair and a very pale pink complexion. According to these norms, a soigné appearance was designed to assist patrician women and female citizens in making an advantageous marriage, and courtesans in attracting wealthy clients.

The women in the portraits displayed the wealth of their family – and thus also of Venice – by means of jewellery and elegant gowns made of costly fabrics. Rendering shining hair and flawless skin was considered by the artists as a special challenge in colouration. Both these features required intensive care by the women themselves, who used ointments containing what we now know to be dubious ingredients (e.g. lead white) and utensils (such as long bodkins) which they kept in ornate caskets.

Elegance in male portraiture

Noble Venetian families had the most distinguished painters portray them in the portego, the prestigious reception room in their palaces. On the one hand, patricians set great store by being recognised as such; on the other, they liked to emphasise their equality of birth with their peers. Thus they would wear apparently simple black robes which, however, demonstrated fine distinctions in the cut and quality of the cloth. The dark garments showed the refined taste of the wearer, while red fabrics – reserved for the few – denoted high social standing.

Titian and Tintoretto revolutionised portrait painting, not only capturing the outward appearance of their subjects, but also lending them dignity and fashionable refinement – rendered by a casual pose and noble dress.

With emotion and conviction

Despite the increasing popularity of works on mythological themes, the vast majority of subjects were religious motifs. Victory over the Ottoman Empire in the Battle of Lepanto (1571) gave additional encouragement to the piety of the Venetians, who saw their way of life validated. In the course of the Counter-Reformation, the Council of Trent had endorsed the significance of religious paintings for the instruction of the illiterate.

This was achieved mainly by portraying scenes designed to touch the emotions of the faithful. Dramatic emotion in paintings showing the Passion of Christ was as much part of the repertoire as the colourful garments in an Adoration of the Kings ‒ in keeping with refined Venetian fashion. Besides rich narratives, artists painted pictures of individual Apostles or saints, bringing viewers close to the subject, inviting their empathy and thus convincing them of the right faith.

Veronese, The Adoration of the Magi, c. 1580/1588

Dramatic moments and inner reflection

Giorgione was a master of creating fascinating pictures in which the narrative is determined by refined contrasts. The composure of the Warrior, who appears not to notice the man emerging before him from the darkness, contradicts the details indicating a potential confrontation – as for instance the man’s hand on the warrior’s arm.

Inspired by such works, Venetian painters executed tension-filled pictures, staging scenes with life-size half-figures filling the pictorial space. These striking paintings show dramatic moments, at the same time exploring the psyche of their protagonists. Despite their triumphs, Salome and Judith seem melancholy, the warriors pensive or tensely concentrating. These motifs were extremely popular with collectors, as demonstrated by Pietro della Vecchia’s Warrior, painted more than a century after Giorgione’s picture.

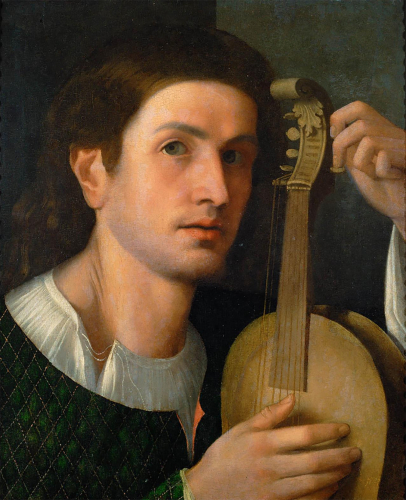

Euphony and harmony

In Venice, music-making was one of the few activities in which both men and women from various levels of society could participate. Many households had several instruments, one of these usually a lute. Painters Giorgione, Paris Bordone, Tintoretto and his daughter Marietta were all considered talented performers. Musicians mixed regularly with artists, writers and scholars, encouraging competition between music and the visual arts.

Mutual esteem was expressed in that painters for the first time elevated their musical colleagues to the status of central subjects of painting. In such pictures they used harmonious chromatic chords ‒ as here Bernardo Strozzi ‒ or ‒ as for instance Capriolo ‒ had the musicians seek the right tone not only in music, but also in love.

Colorito alla veneziana

Venice was one of the principal European centres of the pigment trade. Even patrons and artists from abroad ordered their costly pigments here. These were used not only in painting – the Murano glass-blowers also took advantage of the wide range of colours, producing sophisticated works such as the Puchheim Cup, which were greatly appreciated for their translucency and refractive power.

Inspired by the atmospheric light effects in Venice, artists such as Domenico Fetti painted pictures in vibrant colours determined by the warm light of sunrise or sunset. During his lifetime, Titian was already considered a pioneer of applying paint thickly, with skilful ease, and Jacopo Bassano’s night pieces, with glowing, pastose colours, enjoyed great success. 17th-century art theorist Marco Boschini called their treatment of colour colorito alla veneziana.

Triumph in light and colour

Fontebasso, Pope Gregory I and St Vitalis Interceding with the Virgin Mary for the Souls in Purgatory, c. 1730/31

In the 18th century, artists adopted a new kind of colouration flooded with light, lending fresh stimulus to painting. Sebastiano Ricci harked back to the still much admired art of the Renaissance. The works of Veronese inspired him to use clear, brilliant colours and to lend his figures a timeless elegance.

Ricci’s triumphant success made him the pioneer of Venetian rococo. He and his successors were in great demand far beyond Venice, soon accepting commissions from all over Europe ‒ from Madrid to St. Petersburg. Only one generation later, Francesco Guardi embarked on a different path: in his paintings of the lagoon, he captured the bright light, the changeable weather and the movement of the figures with sometimes fluid, sometimes pastose application of the paint, and his influence continued well into the 19th century.

Società Dante Alighieri: Italy’s language & culture in Salzburg

Società Dante Alighieri: Italy’s language & culture in Salzburg

As an extended supporting program to the exhibition, Dante Salzburg offers the event series “Venice in Salzburg”. It invites all members, course participants, art and Italy fans to an “anno veneziano”, a year of Venice in Salzburg. Here are all the dates: www.dante-salzburg.at

Thanks to

Società Dante Alighieri: Italy’s language & culture in Salzburg

Società Dante Alighieri: Italy’s language & culture in Salzburg